The Reality of Humanism

“When the mind turns its view inward upon itself, and contemplates its own actions, thinking is the first that occurs.” - John Locke

Beowulf

I Have Feet (and other limbs) - The Middle Ages

The Western world developed from a painter’s palate of tribes, regions, and cultures, varying from mile to mile. The accumulated shared language was unrecognizable from today’s understandings, with a flurry of Latin, Swedish, Gaelic, Finish, Danish – to name a few – in a tumult of sounds entirely foreign to modern listeners, or even listeners two hundred years after. When the French invaded and remained for a hundred years, the language altered into something far more recognizable to the modern reader, though stylistically foreign.

At this time, the writings of Britain were few and far between, and it wasn’t until around five hundred years later, the time of the printing press, that more literature began to spread, and the number of those that could read grew, and thus was the Renaissance Era, in terms of literature.

Scholars spend a great deal of time interpreting art, whether it be the paintings found on an ancient cave painted by an ancient civilization, on canvas, stitched into cloth, or the art of the written word.

Art is a form of expression – expression of emotion – love, torment, sadness, anger – of appreciation, beauty, skill, and an expression of the mind.

As Great Britain rose to dominance in the evolving Western world, their thinking became prominent, as did their philosophies. Of course, the Greeks and Romans hold the starting point for the original philosophers of Socrates, Aristotle, and Plato, however, it was during the Renaissance period that the British began to question:

What is Humanism? What does it mean to be human?

Once the question was voiced, the intention behind the question transformed from mind to mind, as did the answer, as did the question itself.

Learning to Talk - Early Modern Humanism

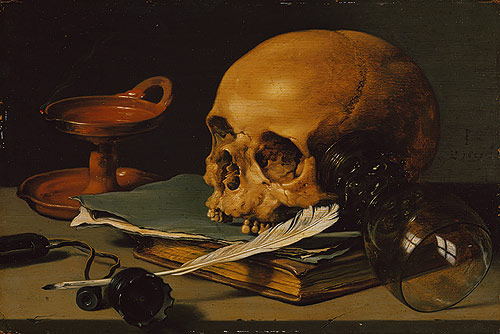

It was said that the birth of analytical thinking began during the Early Modern period. Great minds began to revive the philosophies of Aristotle and Plato. This was a time where the elephant in the room a called out – Death was imminent, lingering, and thus, life should be embraced.

Christopher Marlowe, on the verge of the 17th century brought to the world The passionate Shepherd to His Love, a poem of devotion from a poor shepherd to a being he values so much that only the beauty of nature can garnish her with any justice.

“And I will make thee beds of roses,

And a thousand fragrant poesies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of myrtle.

…The shepherd swains shall dance and sing,

For thy delight each May morning,

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me and be my love.”

(lines 9-12 and 21-24)

However, in a response written by Sir Walter Raleigh called The Nymph’s Reply to the Shepherd, the nymph is dismissive of the shepherd’s confession. The response solemnly reminds the shepherd of her immortality and the frailty of his existence.

“The Flowers do fade, and wonton fields,

To wayward winter reckoning yields,

A honey tongue, a heart of gall

Is fancy’s spring, but sorrow’s fall

…But could youth last, and love still breed

Had joys not date, nor age no need

Then these delights my mind might move,

To live with thee, and be thy love.”

(lines 9-12 and 21-24)

The idea of this time, and for many decades onto centuries, was that mortality is fleeting, that is held as easily as water is to grip. With disease so easily caught between lives, an old age was rare to see. The nymph sees the delicate existence of this man, and turns him away. If she were to love him, he would be just a flutter of her eyelashes in the length of her life.

The immortal turned away from the mortal. During times riddled with sickness, cold and death, would it not be apt to question the presence of the divine upholding humanity’s permanence? Could the depth behind these poems not be the shepherd asking a nymph to love him, but rather asking a divine creature – which one might go so far as to implicate God – to be with him, and said divine creature turning its back to him, God denying him?

While regular prayers were sent to the heavens from undoubtedly each person’s lips, and with Death breathing his icy breath down the backs of each home, the haphazard Devil-May-Care mentality came to fruition – Carpe Diem! Seizing the day to take advantage of life’s pleasures while they were presented and the timing was ripe.

In Robert Herrick’s cheeky ditty, To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time, he is swaying the virgins to let go of the chaste ways and live while living is possible.

“Then not be coy, but use your time,

And while ye may, go marry;

For having lost but once your prime,

You may forever tarry.”

(lines 13-16)

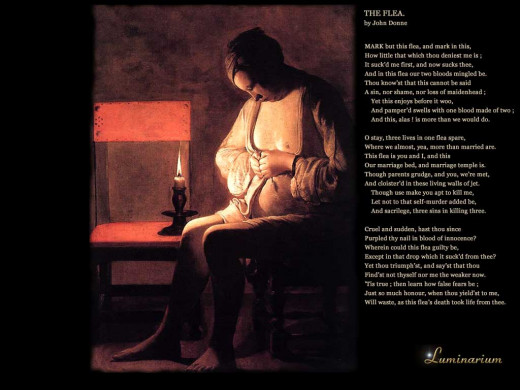

Again the naughty wants of men are displayed in John Dunne’s poem the flea, explaining why he and another are clearly already married since, with great thanks to the flea, their blood had mixed, and thus a copulation of sorts had occurred.

“Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea, our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor same, nor loss of maidenhead…

…’Tis true, then learn how false fears be;

Just so much honor when thou yeild’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee.”

(1-6 and 25-27)

Both narrators of each poem, while cheeky in their intentions, do not deny the reader the reminder of the swiftness of life, of minutes too short, and the imminence of death. With this fact looming overhead, the general meaning of what it was to be human was to indulge in the good things while one could.

Because of the Carpe Diem nature of thought, actions were less faith based. Morality was not of a high concern because it kept one from truly living and enjoying life. Thus it is quite conceivable to believe that the Shepherd is being turned away by God in the response. The great attitude of the time was that humans were self-sufficient, and they could tackle what needed to be tackled, and didn’t need God as much as was once believed (Basics of Philosophy).

Of course the notion and question of what it means to be human did not escape one of the world’s greatest writers in all of history – William Shakespeare. Humanism was a common theme in his work, from soliloquys in Hamlet to the supernatural happenings in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Brian McClinton, author of The Shakespeare Conspiracies, writes in his article “Shakespeare’s Humanism”:

“Hamlet in the early part of the play is a confused and disillusioned idealist. But he matures as he grows older. Ultimately the play challenges Hamlet’s early cynicism. Similarly, the author himself shows progression from the tragedies to the late romances, where the message is quintessentially humanist.” (p. 2)

This broadens the definition of Humanism from seizing the day and man’s self-sufficiency to the human experience.

In Hamlet, the tragic hero experiences the love of his father and mother, the love of the kingdom, the love of Ophelia, betrayal from family and friends, anger, loss, mourning, confusion, power, justice, and at the very end of the play with the kingdom in good hands, Hamlet experiences righteousness. These are all emotions and experiences which could arguably be limited only being human.

A common theme in Shakespeare’s works is the contemplation of death and the tragedy of failure, as many of his plays are tragic. Could it be that while he believed in the characteristics of literally what made man man, he mocked the core belief of self-sufficiency of Humanism?

The calamity of his more serious pieces dance along human weakness – the silliness of the heart which draws to focus rage and jealousy, the craving of political power the drives one to murder, the ego that when hurt rises to revenge, and so on.

Between Marlowe, Dunne and Shakespeare, the understanding of what it is to be human is clear: arrogance to lead to the separation of reliance upon God, and the ego which leads to one’s demise.

“That all our knowledge begins with experience there can be no doubt…The conceptions of pure reason are not obtained by reflection, but by inference or conclusion.” (Kant p.1 and 96)

Learning to Use Tools - The Restoration Era

While the philosophy of defining the meaning of what it is to be Human might not have been as prominent during the Reconstruction Era, or rather, not the forethought of literary minds, it was still a driving force, in one form of another. This was a time which began to sway towards the Natural Laws, studied at length by Sir Isaac Newton, which briefly lead the focus away from Christian beliefs.

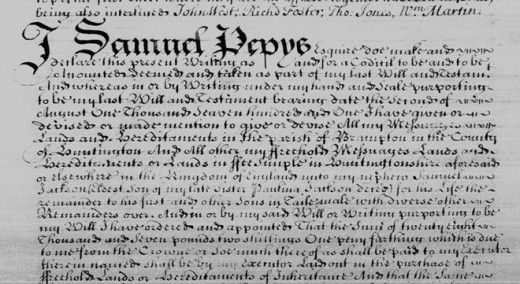

Reason and Logic were the prominent ideas during this time, and perhaps thus was the drive for Samuel Pepys to begin his nine-year long project.

It was Pepys that began the acting of a daily jotting of activities and ideas, keeping record of musings and the like. This was the first diary as we know it. While he may or may not have consciously been playing into it, through ritualistic recording of thought, one understands the(ir) psyche more, and thus, on some level is discovering what it is to be human, at least in a personal realm of reality.

The magnitude of this daily act could never have been foreseen as the trend caught on - the psychology behind daily tallying of activities even being studied in our current, technology riddled lives. While at the time, the regular journaling could have been no more than listing the stops made and people spoken to without detail of conversation, today we indulge in regular updates on social media such as Facebook, Twitter, Pintrest, Instagram, blogs – allowing the world to see our daily habits.

During this time, written detail was beginning to take form, though would fully flourish during the Romantic Period. However, one of the forerunners of this movement was Pepys.

“He implicitly commits himself to tracking the whole day’s experience: the motions of the body as it makes its way through the city in boats, in coaches, and on foot, and the motions of the mind as it shuttles between business and pleasure.” (Masters of British Lit. p.1041)

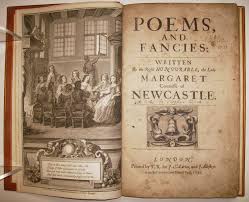

During this time as well, the Duchess of Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish, ventured forth into the men’s world, publishing a book of poems, and openly voicing her fears at doing so. Though in an effort to defend her book of poems which served as her own versed diary as well as a window into her imagination (“fancy”), she wrote:

“If you wonder that I join a work of fancy to my serious philosophical contemplations, think not that it is out of disparagement to philosophy, or out of an opinion as if this noble study were but a fiction of the mind…the end of reason is truth, the end of fancy is fiction. But mistake me not when I distinguish fancy from reason; I mean not as if fancy were not made by the rational parts of matter, but by ‘reason’ I understand a rational search and inquiry into the causes of natural effects, or rather ‘fancy’ a voluntary creation or production of the mind, both being effects, or rather actions, of the rational part of matter, of which, as that is more profitable and useful study than this, so it is also more laborious and difficult, and requires serious contemplations.” (Masters of British Lit. p.1053)

It is from her letter to the reader that we gain the insight of the want of reason, as well as the importance of maintaining imagination to propel forward, though the two not to be confused.

In the epilogue, “To the Reader,” she calls the reader her “Platonic Friend”. This was a time for the search of truth, and the philosophy of Plato revolved around Truth, with the utmost capital of T’s. Cavendish’s writing not only breaks the mold of the male role in writing, but she also expects her readers to be of a similar mind set – the search of truth, and of breaking boundaries. What’s more, she is venturing into the tends of philosophy to come – the power of the imagination (which we will explore in the Romantic Period). She believes the power of the imagination is just as demanding as that analytical and philosophical mind, as it is through the imagination that ideas are developed.

The minds of the Restoration Era was that of Reason. So much so, that even John Wilmot, in an effort to mock those that seek answers to the unanswered questions, wrote a lengthy poem titled, A Satyr Against Reason and Mankind, which exclaims thinkers to waste their life away, deny themselves the pleasures of living, and spend fortunes on school, ink and parchment. Yet, reasonably concludes his own philosophical conclusion:

“But a meek, humble man of honest sense,

Who, preaching peace, does practice continence;

Whose pious life’s a proof he does believe

Mysterious truths, which no man can conceive.

If upon earth there dwell such God-like men,

I’ll here recant my paradox to them,

Adore those shrines of virtue, homage pay,

And, with rabble world, their laws obey.

If such there be, yet grant me with this at least:

Man differs more from man, than man from beast.”

(Lines 212-221)

Wilmot was a man of action, one who loved his wife passionately and fought battles on the sea, became belligerently drunk and destroyed royal artifacts – a “bloke’s bloke” and the height of fascination of the court – and thus, not one who dwelt on the questions of the universe. The irony resides in that he took the time to draft a well thought out and witty poem of 221 lines explaining why one ought not to waste their time thinking all the time – which of course took some thought to compile. What’s more, while bloke-ish the Earl of Rochester might have been, he still went down in history as a poet, practicing that which makes human human: art.

Art of the Restoration Era

Reading of "The Lady's Dressing Room" By Jonathan Swift

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, The Reasons that Induced Dr. Swift toWrite The Lady's Dressing Room

A response written by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, a satirical response to Swift's "The Lady's Dressing Room", explaining why he sought revenge enough to write such a vile poem to depict women so poorly.

A vastly large part of the Restoration period was its resonance in politics. The idea of freedom was gaining popularity, and democracy for the people. The consideration that freedom was a born right and not gifted from the higher classes, and basic human rights were gaining more focus. As mentioned before, this was the beginning of the fight for women’s rights, against slavery, and the need for justice.

Poems such as Jonathan Swift’s, The Lady’s Dressing Room – which, in great detail, outlines the disgust and horror of a man who snooped in a woman’s dressing room and found that she too produced the same bodily functions as a man, and was in fact human – used satyr to display the foulness of women (which matched that of men), and humanized these pedestalled beings. Regardless of Swift’s intentions and placement in the political battle of equality, his poem raised awareness, as well as offence, which inspired another woman writer to respond (with poem which mocks that masculinity of man).

A History of Western Philosophy - The Romantic Movement

The Sublime

Learning to Write - The Romantics

The writings of the Romantics are shrouded in aesthetics – pages and pages of descriptions of nature, odes the grandeur of the natural world, humbled voices of the frail human body against the awe-inspiring and terrifying magnitude of Nature.

As mentioned previously with Margaret Cavendish’s defense of fancy, the imagination became the defining idea of humanism. While the imagination could create worlds of splendor, the surrounding world inspired Edmund Burk’s annotation of the sublime.

“Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. I say the strongest emotion, because I am satisfied the ideas of pain are much more powerful than those which enter on the part of pleasure. Without all doubt, the torments which we may be made to suffer are much greater in their effect on the body and mind, than any pleasures which the most learned voluptuary could suggest, or than the liveliest imagination, and the most sound and exquisitely sensible body, could enjoy.” (Burk p.110)

This idea of the sublime inspired literature of the time – not just in praising the enormity of nature, but in humanity as well, as seen beautifully in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

While an obvious theme in the classic novel revolved around Dr. Frankenstein pushing the boundaries of nature, the appreciation and fascination of the grotesque and sublime were also prominent. In modern times, should a creature be built and reanimated, no matter how monstrous in appearance, it would be regarded as a being of beauty for the scientific success it represented. The creature in the novel was in fact, a perfect representation of imagination come to fruition and the sublime – something terrifying, yet beautiful. The creature, in the face of constant rejection, used reason and logic and developed compassion and yearning for love and acceptance, and only after several years of being verbally and violently turned away, did he himself choose to become the monster society believed him to be.

Coupled with Immanuel Kant’s idea of beauty being a projection of experiences, this imaginative tale captures the philosophies of the Romantic Period in a neatly bound book.

After the previous 400 years building the arrogance of man – seizing the day without worry of wrath of God, crying out for equality, and mocking political figures and systems – the Romantics fell to humility at the powers beyond them: Nature and Time. This understanding lead to Transcendentialism: the belief in connecting to something much greater than the self, and that one could get past the physical limitations through pursuit of mind. It was this mentality that also name this time the Enlightenment Era.

This push for the development of mind supported the love of the imagination as well. William Blake was quoted saying:

“If we see with our imaginations, we see the infinite; if we see with our reason, we only see ourselves.”

Percy Shelley valued the mind to such extent, he wrote a poem called A Hymn to Intellectual Beauty, in reference to “The ideal Spirit apprehended by the mind” (Masters p.474). Filled with nature imagery, and laments the inability for it to be tamed, yet coincidedly celebrates the same.

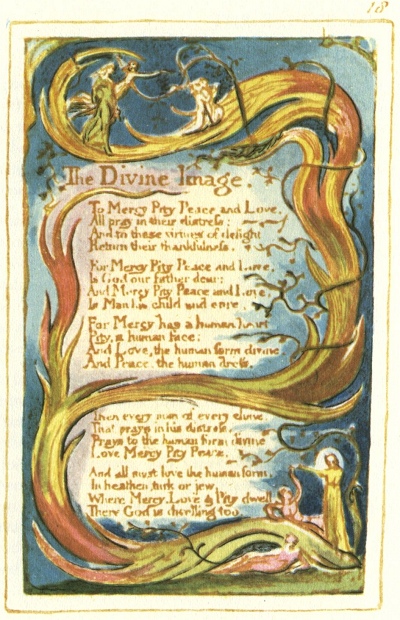

Science, too, was taking a greater hold at this time, and calling upon the questioning of God and justice. In William Blake’s dualistic collection of poems called Songs of Innocence ad of Experience, he divides the artistic views between the naïve “understandings” of the world with those that have been altered by truly living in the world. The poem, The Divine Image in Songs of Innocence, Blake writes about how man was made in the image of perfection – “Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love.”

“And all must love the human form,

In heathen, turk or jew.

Where Mercy, Love & Pity dwell,

There God is dwelling too.”

(lines 17-20)

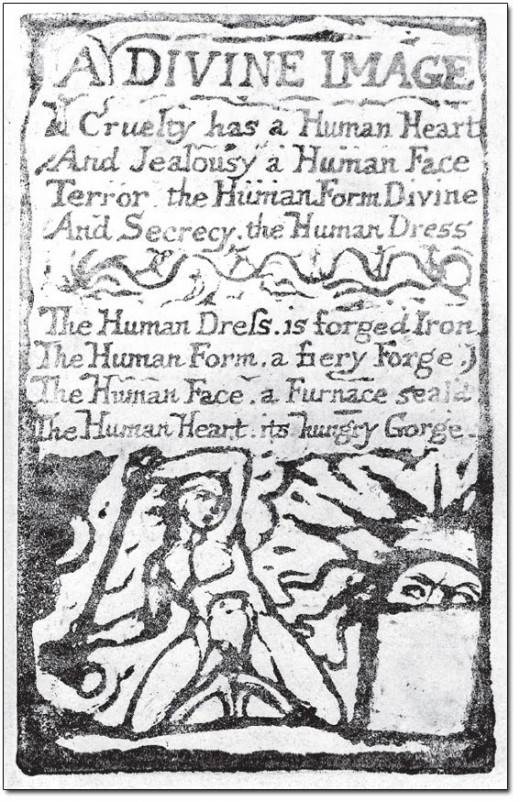

However, in a similarly titled poem, A Divine Image in Songs of Experience, the depiction takes on a vastly different tone.

“Cruelty has a Human Heart

And Jealousy a Human Face

Terror, the Human Form Divine

And Secrecy, the Human Dress.

The Human Dress, is forged in Iron

The Human Form, a fiery Forge

The Human Face, a Furnace seal’d

The Human Heart, its hungry Gorge.”

This vastly contrasting depiction show the difference between what we are told and what experience teaches us – though some might easily argue that both depictions are still divine. With God being portrayed throughout history and religion as being both merciful and vengeful, each poem shows a side of the coin.

“That is what the highest criticism really is, the record of one’s own soul.”

~Oscar Wilde

THe Lady of Shalott

- The Lady of Shalott (1832) by Alfred, Lord Tennyson : The Poetry Foundation

Part I / On either side the river lie / Long fields of barley and of rye, / That clothe the wold and meet the sky;

Development of Identity - The Victorian Age

Discovery is the reward for curiosity which drives us forward, and thus was the philosophy of the Victorian Era. It was deemed the “age of self scrutiny” (Masters p. 585). It was an era of speed as the Industrial Revolution took hold, and England became lined with rail tracks, carrying supplies, passengers and mail. Even the speed of advancement increased – the population doubled during this time, steamships began crossing large bodies of water creating greater trade, and photography came into play.

Publishing began escalating as well, and thus more people were reading, and the amount of literate people reached 97% of both genders. With the ability to read and speedier technologies taking way, more time could be used for self discovery.

However, with the self under examination larger questions of social morality were being neglected. Thomas Carlyle was quoted saying:

“Close thy Byron and open thy Goethe.”

The introspective natures which lead to the acquired label of “Age of Self-Scrutiny” was neglecting the ability or wonton to strive to improve society. As Humanism was developing over the centuries, this altered what it was thought to be. The self deprecation turned outward, and the fight for equal rights (mostly women) resumed.

Alfred Tennyson portrays the disposition of women in his poem The Lady of Shalott, in which a woman, who has been confined to a room in a tower to weave tapestries her entire life, leaves her tower only to realize her curse, and dies trying to reach Camelot. The tower, acting as a representation of the social restrictions placed upon a woman, and the weaving of the tapestries her very strict role in life, the ending stanza displays the dismissive attitude of the man-dominated world in response to the struggle of the women trying to break free:

“Who is this? and what is here?

And in the lighted palace near

Died the sound of royal cheer;

And they cross’d themselves for fear,

All the knights at Camelot:

But Lancelot mused a little space;

He said, “She has a lovely face;

God in his mercy lend her grace,

The Lady of Shalott.”

(line 163-171)

The Lady of Shalott

Magic - Jean Thompson

Silent brilliance all around,

Muffled footsteps make no sound

But scrunch of snow beneath my tread.

The dog, exuberant, bounds ahead.

While no-one drives, the lane is mine,

Past bushes bowed to new design,

Leafless trees with blanket white,

Rooftops iced for my delight.

So brief a stay, it cannot pall,

This gentle mantle over all,

Enchanting in its pristine hue,

Which gilds the humdrum daily view.

I marvel with my heart aglow;

Such magic from a fall of snow.

Applying the Self - Where Did We End Up?

The question of Humanism has slowly evolved through time, or rather, the different viewpoints have been analyzed. From the understanding that life is short, and adopting the Carpe Diem mentality of not allowing time or moments or experiences go to waste; to the belief that it was Reason that was the key to greatness and the defeat of ignorance; to the realization of the vastness beyond the human self, and being humbled by the sublime; we have pulled together pieces of the puzzle to attempt to create an answer.

But is the question the same these days than it was in the past?

With quantum theories become more prominent in our discoveries, perhaps the question no long is “What does it mean to be human?” but instead, “What is reality?”

Each literary example supporting or displaying the aforementioned ideas came from different background, different time periods, had different lives, different struggles, and thus had different viewpoints. They each wrote from what their perception of the world was, and thus, wrote about the reality they experienced. If each experience is different, then how can one assume humanism is all-encompassing and applicable to each individual? Thus, the question has evolved to the questioning of the fabric of Reality.

It is through the questioning of our Humanism throughout the centuries and on to our current questioning of reality that we can develop our consciousness as a worldwide basis. Without understanding what it is that makes us us, then we have no understanding of the reactions we have, predicting the best for humanity, or developing past our basic instincts all together.

Alan Watts - Philosophy and Society - What is Reality

Work Cited

Basics of Philosophy. The Basics of Philosophy: Humanism. 2008. Web. 2 December 2014. <http://www.philosophybasics.com/movements_humanism.html>.

Burke, Edmund. "Burke's Writings and Speeches." n.d. Gutenburg.org. Web. 3 Dec. 2014. <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15043/15043-h/15043-h.htm#Page_110>.

Damrosch, David, et al. Masters of British Literature. Ed. Joseph Terry, et al. Vol. A. New York, San Francisco, Boston, London, Toronto, Sydney, Toko, Singapore, Madrid, Mexico City, Munich, Paris, Cape Town, Hong Kong, Montreal: Pearson Longman, 2008. 2 vols. Print. September 20114.

Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. London: Penguin CLasics, 1997. Print. 3 12 2014.

McClinton, Brian. "Shakespeare's Humanism." July 2006. Humanistni.org. Web. 2 December 2014. <http://humanistni.org/filestore/file/shakespeare%20humanism.pdf>.

Thompson, Jean. "Magic." The Lady 29 January 1987: 216. Print.